护联中心新设135万元基金 打造更“好玩”乐龄护理

如何鼓励年长者更积极地投入社交,活出精彩的老年生活?护联中心推出新的135万元基金“FUN! Fund”,鼓励业者把“好玩”融入乐龄护理计划。

配合11月1日的社区护理日,护联中心星期五(11月4日)举办社区护理领导系列,并在活动宣布推出新基金

“FUN! Fund”由护联中心和新加坡社区基金会联合成立,致力于改善乐龄人士所面对的社交孤立现象,进而提升他们的身心健康。

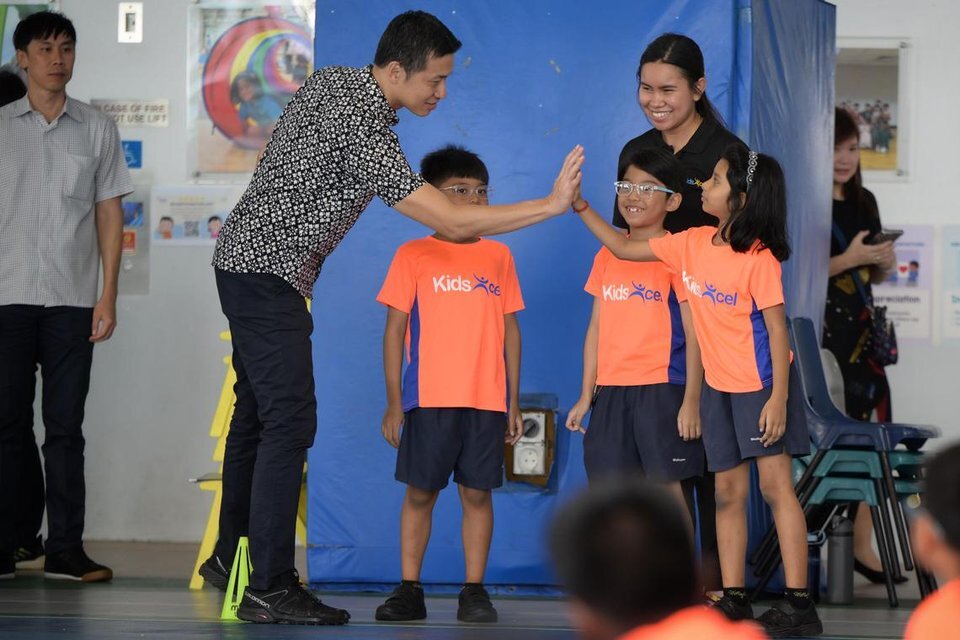

社区护理业者可呈交计划书,提出创新的活动点子来带动乐龄人士的情绪,鼓励他们积极尝试新事物。例如,太和观庙弯活跃乐龄站推出“虚拟游乐场”,通过高科技系统和怀旧元素的“新旧”结合,带给乐龄人士别具特色的玩乐体验。

每项计划可获得高达五万元的资助款项。

除了成立基金,护联中心和新加坡社区基金会接下来三年也将在社区护理的四大方面展开合作,分别为:活跃乐龄、环境和社区空间、人力和业务连续性。

阅读更多:Fun! Fund

信用:联合早报©新报业媒体有限公司。复制需要许可。

如何鼓励年长者更积极地投入社交,活出精彩的老年生活?护联中心推出新的135万元基金“FUN! Fund”,鼓励业者把“好玩”融入乐龄护理计划。

配合11月1日的社区护理日,护联中心星期五(11月4日)举办社区护理领导系列,并在活动宣布推出新基金

“FUN! Fund”由护联中心和新加坡社区基金会联合成立,致力于改善乐龄人士所面对的社交孤立现象,进而提升他们的身心健康。

社区护理业者可呈交计划书,提出创新的活动点子来带动乐龄人士的情绪,鼓励他们积极尝试新事物。例如,太和观庙弯活跃乐龄站推出“虚拟游乐场”,通过高科技系统和怀旧元素的“新旧”结合,带给乐龄人士别具特色的玩乐体验。

每项计划可获得高达五万元的资助款项。

除了成立基金,护联中心和新加坡社区基金会接下来三年也将在社区护理的四大方面展开合作,分别为:活跃乐龄、环境和社区空间、人力和业务连续性。

阅读更多:Fun! Fund

信用:联合早报©新报业媒体有限公司。复制需要许可。

- Related Topics For You: AGEING WELL, CHARITY STORIES, COLLABORATION, COMMUNITY IMPACT FUND, DONOR STORIES, EVENTS, FUN! FUND, NEWS, PARTNERSHIP STORIES, SENIORS

.jpg)