Collaborative Giving to build Community Mental Health Champions

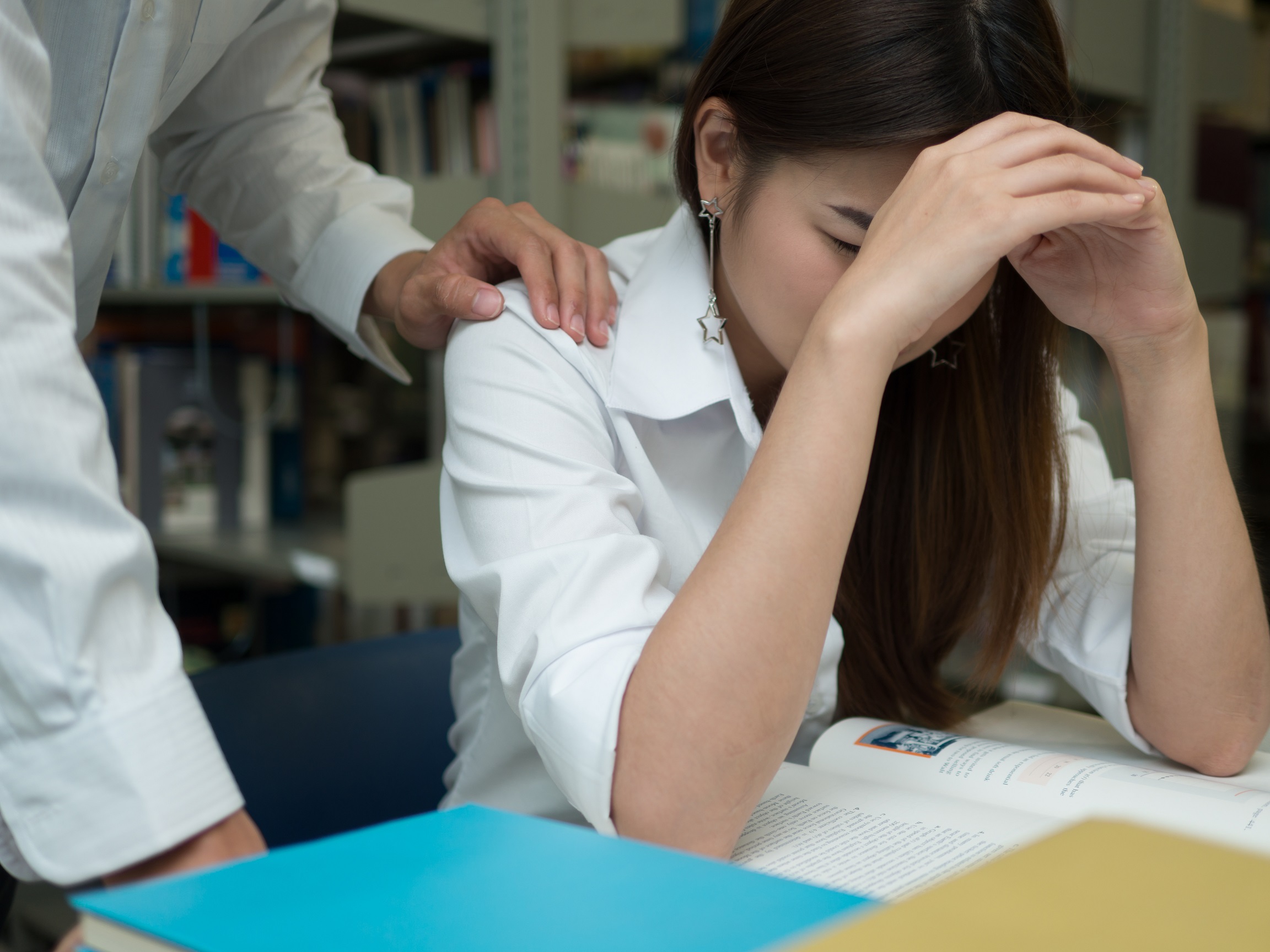

The Community Mental Health Champions Initiative, a collaborative project by the Community Foundation of Singapore (CFS) and Empact and supported by our corporate partner. It aims to recruit, train and retain 1,000 community mental health champions. Through this initiative, we will build a pool of mental health champions. These champions will actively support the sandwiched generation with a listening ear and signposting to professional services when needed – helping more people prevent or access support for mental health issues.

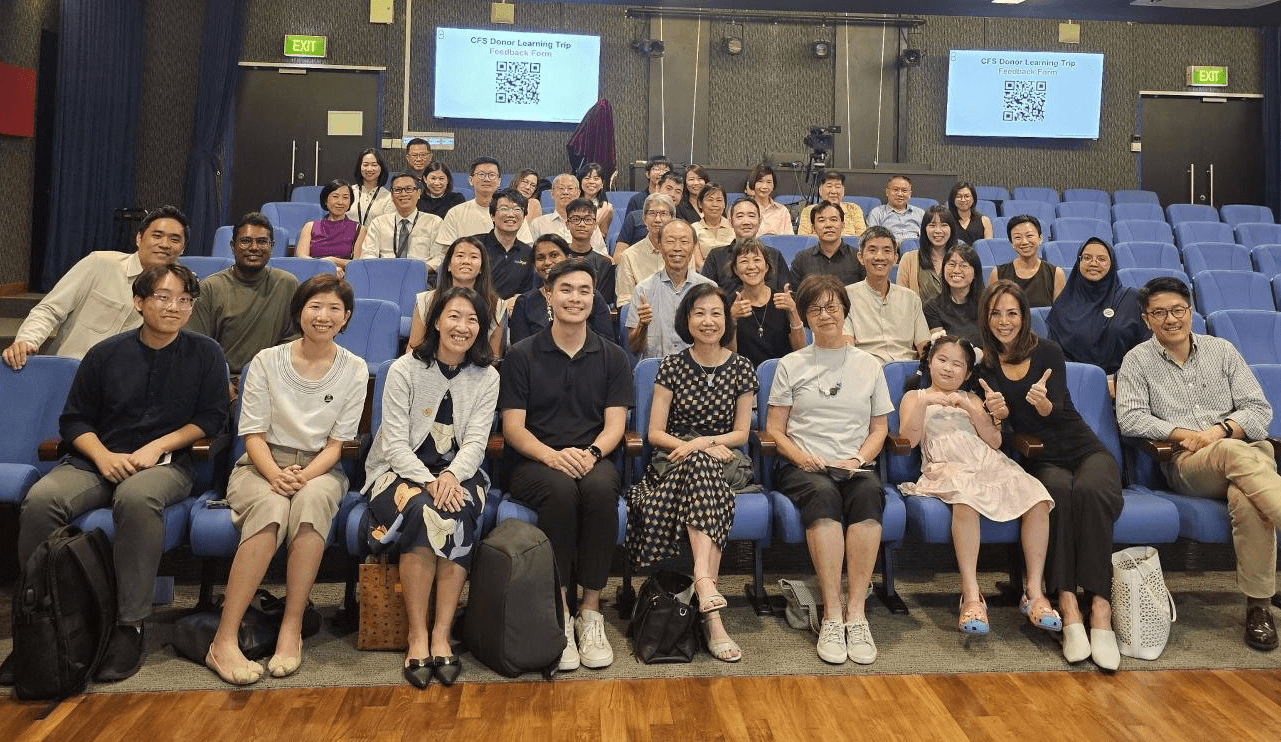

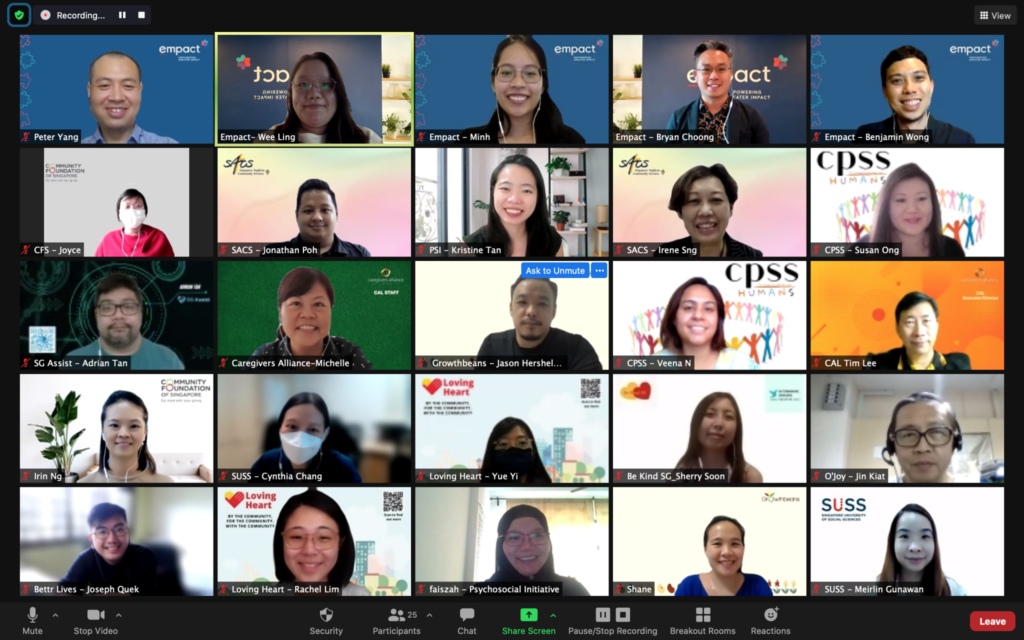

The Community Mental Health Champions Initiative is carried out in two phases – Design Phase and Implementation Phase. During the design phase, eleven organisations will come together for a series of workshops to share their knowledge and build a collaborative understanding on issues regarding mental health and how to equip these champions. These eleven organisations are Be Kind SG, Bettr Lives, Caregivers Alliance, Community of Peer Support Specialists, Growthbeans, Loving Heart, O’Joy, Psychological Initiative, SG Assist, Singapore Anglican Community Services, Singapore University of Social Sciences.

These workshops enable the organisations to align a common vision – mental health promotion intervention – and create opportunities for shared knowledge. Started on 9 July, the first workshop began by defining the Sandwiched Generation. Last week during the second workshop, the organisations shared about mapping and understanding the overall mental health support ecosystem.

Find out more about how you can be part of this initiative or about collaborative giving here.

The Community Mental Health Champions Initiative, a collaborative project by the Community Foundation of Singapore (CFS) and Empact and supported by our corporate partner. It aims to recruit, train and retain 1,000 community mental health champions. Through this initiative, we will build a pool of mental health champions. These champions will actively support the sandwiched generation with a listening ear and signposting to professional services when needed – helping more people prevent or access support for mental health issues.

The Community Mental Health Champions Initiative is carried out in two phases – Design Phase and Implementation Phase. During the design phase, eleven organisations will come together for a series of workshops to share their knowledge and build a collaborative understanding on issues regarding mental health and how to equip these champions. These eleven organisations are Be Kind SG, Bettr Lives, Caregivers Alliance, Community of Peer Support Specialists, Growthbeans, Loving Heart, O’Joy, Psychological Initiative, SG Assist, Singapore Anglican Community Services, Singapore University of Social Sciences.

These workshops enable the organisations to align a common vision – mental health promotion intervention – and create opportunities for shared knowledge. Started on 9 July, the first workshop began by defining the Sandwiched Generation. Last week during the second workshop, the organisations shared about mapping and understanding the overall mental health support ecosystem.

Find out more about how you can be part of this initiative or about collaborative giving here.

- Related Topics For You: CHARITY STORIES, COLLABORATION, COLLECTIVES, DIRECT AID, DONOR STORIES, EVENTS, GROWTH COLLECTIVE, HEALTH, MENTAL WELLBEING, PARTNERSHIP STORIES